This content is for Premium Subscribers only. To view this content, login below or subscribe as a Premium Subscriber.

Related News Articles

Traxtion Is Meeting Rail Needs Through Innovation and Sustainability

22 April 2025

SADC, South Africa

3 min

Essential Equipment Starts Arriving at the Cape Town Container Terminal

22 April 2025

SADC, South Africa

1 min

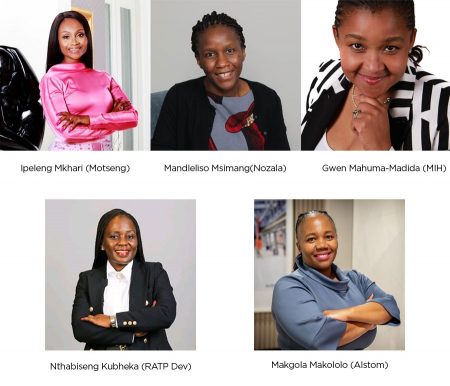

Black Women-Led Companies Driving South Africa’s Mobility Transformation

07 April 2025

SADC, South Africa

3 min

2 min

2 min

1 min

South Africa’s Department of Trade Aims to Sustain Localisation Momentum

05 April 2025

SADC, South Africa

2 min

2 min

Private Sector Called to Participate in Rail and Port Sector Reform

31 March 2025

SADC, South Africa

1 min

Gautrain Expansion Set to Boost Gauteng’s Economy and Transport Network

31 March 2025

SADC, South Africa

6 min

2 min